Today is Labor Day, and it is a holiday that has particular significance for railroad labor. Spike was reminded of this earlier today when a Seattle Times column described the efforts of a self-described local think tank to boycott the holiday. So what does it have to do with the railroad?

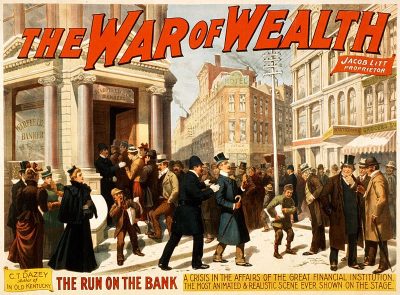

Play “War of Wealth” dramatized the Panic of 1893 when it opened in February 1895. Original image in Library of Congress.

1893 was a difficult year for the United States: the worst economic recession in the country’s 117-year history gripped the Nation. Two of the chief culprits causing the “Panic of 1893” were railroad speculation and over-building. More than 500 banks and 15,000 businesses failed, including the mighty Union Pacific Railroad; the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad; the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway; and the Northern Pacific Railroad. The latter company had its western terminus in Tacoma, and had recently leveraged itself to acquire control of the Seattle, Lake Shore and Eastern Railway (“SLSE”). (The SLSE’s mainline between Snoqualmie and North Bend is today owned by the Northwest Railway Museum.) The Panic of 1893 was devastating for railroad suppliers too.

George M. Pullman was the founder and president of the Pullman Palace Car Company. In 1880 he conceived and developed the Town of Pullman, Illinois as a model community that would attract the best and brightest employees by providing ideal living conditions. When initial construction was completed in 1884, the town included more than 1,000 homes, public buildings, and many parks. Pullman workers rented homes from the company; the fee included basic home maintenance and even daily garbage collection. The community was independently viewed as a nearly perfect town, but residency for employees was less than optional: during a work slowdown, employees who lived outside the town of Pullman were the first to be laid off.

Pullman strikers outside arcade building. Original image from Abraham Lincoln Historical Digitization Project.

The economic recession continued and by early 1894 Pullman reacted to the situation by reducing wages by an average of 25%. Rental fees for company housing, however, remained unchanged so some worker’s pay was reduced to just $9.07 a fortnight, but rent was $9.00 leaving just 7 cents for food, water and gas. And a workday remained at 16 hours. On May 10, 1894, workers who were now represented by the American Railway Union (“ARU”) voted to strike. Six weeks into the work stoppage, Pullman – who had guaranteed the investors of his model town a 6% return on investment – continued to refuse requests for negotiation or arbitration. The ARU expanded the impact to a boycott by all their members of all Pullman Palace Cars operating in 27 States, ultimately involving 250,000 workers. This effectively shut down most of the railroads west of Detroit, stopped the mail, and – with telegrams from railroad managers demanding action – got the attention of President Grover Cleveland, who ordered his Attorney General to act. Federal Marshalls – strangely, paid and under the control of railroad company managers – and as many as 12,000 army troops were called in to enforce the America’s first-ever back to work order. Predictably, violence broke out, resulting in the death of at least 30 people and causing millions of dollars in physical damage and lost opportunity. The boycott ended by mid-July; union leaders were jailed for violation of the injunction; but the strike against the Pullman Palace Car Company did not end until August 2.

1894 was a midterm election year. In the shadow of the Pullman strike and boycott, a concession to labor: on June 28, 1894, a bill creating a national holiday called Labor Day, to be observed the first Monday of September every year, was approved by Congress and signed by the President. Interestingly, the law was silent on the subject of holiday pay, an almost completely unknown concept in 1894.

[images are from Wikipedia Commons and are public domain due to age]