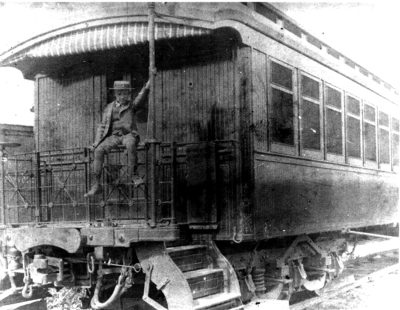

Chapel car 5 Messenger of Peace with its distinctive open vestibules or platforms.

A distinguishing feature of many 19th Century railroad cars is an open platform or vestibule on one or both ends. For chapel car 5 Messenger of Peace, this platform was the ingress and egress to the car. So the preacher, his wife, and all the parishioners used the open-end platform to enter and leave the car. Clearly, restoration of this missing feature was vital for a successful project, and was fully supported by the major funders including Save Americas Treasures, the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Partners in Preservation (Seattle) and the Washington State Heritage Capital Projects Fund administered by the Washington State Historical Society. And it was one of the most challenging aspects of the project because most of the work had to be performed in a specific sequence between March 2011 and April 2012 to avoid conflict with other work divisions such as carbody rehabilitation, floor repairs, and even the Terne roof installation.

“Badly deteriorated” was the entry made in the initial survey. Little remained in place from the original platform.

Vestibules in general are highly susceptible to deterioration. Open platforms are even worse off. Every rainstorm, passing insect, or even passing thief has open access. For instance, when the car was just a few years old, the pastor woke up one morning to learn that his milk can had been stolen from the end platform. Apparently, that Sunday’s sermon reminded parishioners that “thou shall not steal!”

The only surviving section of the original platform end beam (top) is compared with the new end beam (bottom).

The Messenger of Peace had very little to offer about the platform to researchers and rehabilitation specialists as they put their work plan together. Fortunately, a portion of the original end beam had been recovered from the seaside where the car was used as a cabin; it confirmed the basic dimensions. One end of the car had nearly complete platform and draft sills and those were used to make copies.

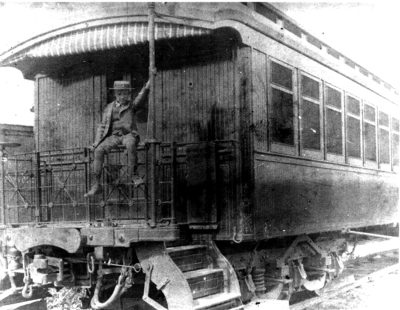

“B” end of car 5 at Novinger, MO. Image courtesy of Adair County Historical Society.

Other resources played an important role too. Researcher’s visited other Barney and Smith-built cars from the era looking for clues, but most other cars had been retrofitted with more modern accessories from the early 20th Century. The Adair County Historical Society had a wonderful photo of the end platform taken in circa 1903 at Novinger, MO and this proved to be the most valuable guide.

New platform and draft sills are attached to the car with new fasteners

Once basic dimensions were established, the rehabilitation team’s next challenge was to find large dimension white oak timbers, the species originally used for the chapel car platform and draft sills, and platform end beam. Oak is an unusual wood for its density, resistance to decay, its hardness, and for the challenges in drying green wood. A phenomenon called cell collapse often occurs when forcing large oak timbers to dry and severely reduces strength. Air drying of green oak timbers is effective but takes years. So what to do? Recycled oak beams from an Amish barn in Ohio!

A platform end beam is milled on the Northfield chain mortiser.

The timbers arrived in mid-winter and the team found they had been stored outside. The timber was cleaned off and any remaining fasteners were removed. Holes or other minor defects were filled with epoxy or wood plugs were glued in. Then the process of preparing the timbers began.

A large slick was used to clean up the initial cuts made by the mortise machine There is always a need for good hand tools when rehabilitating old wood cars!

Four large men were required to guide the 500-pound timbers through the Oliver planer. During this process, several pockets of insect damage were discovered which had to be treated and repaired. But in the end, some really great looking timbers were produced for the chapel car.

Just a sample of the steel hardware that is unseen inside and beneath the platforms.

Was there more to it? Well, yes. One of the unsung heros of the project was Ray M. who repaired or made new the steel tension and tie rods that hold everything together. Original steel was used wherever possible and was connected to new material with a turnbuckle. Ray spent many hours custom machining hardware to fit in tight places where it would not be noticed.

There were also new castings required to make it all work. Fortunately, there was at least one copy of everything so the team was able to work with Mackenzie Castings in Arlington, WA to have copies made in ductile iron. And they did fabulous work too!

The end railing is missing from the car and will have to be fabricated. Fortunately, the great folks at Prairie Village in South Dakota have allowed the Messenger of Peace researchers to photograph and measure the railings on their chapel car Emmanuel. These railings appear to be identical to the Messenger of Peace but surprisingly a number of other details including the platform end beam design and layout are not exactly the same even though the cars were built to the same plan. The railings will be fabricated when additional project funding is secured.

The lead rehabilitation specialist Kevin P. guides the mounting bolts for the platform end beam into the matching holes.

Platform and draft sills are approximately 16 feet long. The platform end beam is the width of the car and weighs over 200 pounds. So a lot of special handling was required to maneuver the timbers around to the other woodworking machines. And in the end – or at least as of May 2012 – the Messenger of Peace has regained its platform to preach!

The completed open vestibule needs one more detail: an end railing. When more rehabilitation funding is secured, a replacement railing will be fabricated