The original Terne roof was applied in 1898. Pin holes, loss of coating and breaches in the membrane left few options for the rehabilitation.

The roof on a century-old railcar is more than just something to keep the rain out; it is a distinguishing feature. On chapel car 5 Messenger of Peace, the roof is particularly important for what it was made of: Terne metal. The vast majority of 19th and early 20th Century rail passenger cars had a canvas roof supported by a wooden deck. The chapel car was built with a 28-gauge Terne sheet metal roof supported by a wooden deck. It debuted in its natural state and over a short period of time oxidized to a pleasant pewter-like appearance. In later years as the roof began to show its age, it was coated with paint and other materials to seal leaks.

Original Terne sheet metal produced by Piqua in 1898. The pewter-like appearance is oxidation accelerated by air pollution. The seams were sealed with lead solder.

Terne metal has been around for more than 200 years and in its earliest form was sheets of wrought iron coated with an alloy of tin and lead. Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello was roofed with Terne metal at his request, and other important 19th Century structures that were built to last also received the same treatment. As technology improved, Terne roofing was offered as light sheet metal with its corrosion-resistant coating on both

sides. Lightweight Terne roofing could be used in a variety of lighter constructs – such as a railcar roof.

Original sheet metal roof was carefully torn up to allow repair of the deck. The “holes” behind Gary were for the kerosene lamp chimneys.

Chapel car 5 was built with a traditional Terne-coated 28-gauge carbon steel roof. The light gauge sheets performed for more than 100 years but by the time the car arrived at the Museum, the sheets were heavily compromised with pin holes. Complicating how this would be mitigated was the unknown condition of the underlying decking: the only way to inspect and

repair was to remove the metal sheets. It was not practicable to remove the original sheets and reuse them. And the Museum’s concern was justified: several areas of previously undetected deterioration were discovered as the original Terne metal was removed. The ends hoods in particular had issues and new “green” white oak lath was steamed and applied to the damaged areas to rehabilitate them as new.

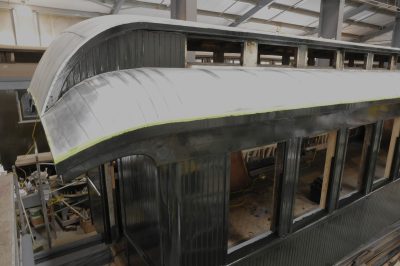

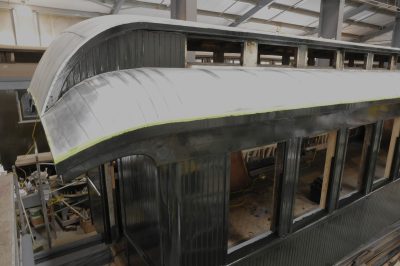

New panels on the upper deck. Metal will be kept in its natural state in keeping with the original treatment.

A team of two sheet metal specialists applied the new Terne II sheets. The center panel of the upper deck slid over the two side panels.

So what is the Terne coating? Originally it was an alloy of approximately 79% lead and 19% tin. So why tin? Tin allows the molten lead to “stick” to the carbon steel, which it ordinarily would not. The other 2% of the alloy is additives such as antimony to adjust characteristics such as melting point. Today, a concern over lead in the environment has evolved the product into an alloy of zinc and tin, which is now known as Terne II and is manufactured by Follansbee. Seams of Terne II sealed with tin solder.

The hoods on the ends of the roof were particularly challenging.

The new Terne II metal was available to the Museum in a coil steel format. So large coils were purchased, sheared by sheet metal specialists, and each edge bent to 90 degrees. Individual sections of roofing are connected to each adjacent panel by folding the edge of the panel over the edge of the next panel and rolling it smooth. The seam was soldered with tin to complete the seal; work was performed by Trinity Sheet Metal of Granite Falls, WA. In all, more than 1,800 linear feet of soldering was required to complete the roof. The new roof – as with the original – will be left uncoated and untreated. Over time it will oxidize to a pewter-like patina, though ironically because of cleaner air today this process will take considerably longer than it would have in 1898.

The completed roof is striking and a is an appearance not seen for generations.

Spike, Well I sure learned something new today…terne metal… The detail and dedication involved in just reconstructing the roof of the chapel car is a bit mind boggling. The result is very striking… Take Care, Big Daddy Dave

This comment has been removed by the author.

I admire the valuable information you be offering for your articles. I will be able to bookmark your blog and feature my children test up right here generally. I'm relatively sure they're going to be informed a variety of new stuff here than any one else! Flat Roofs North East

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.